The Way We Were: William H. Rose

William Rose has a lifetime of memories and a postcard art collection that allows him to see Jacksonville through the eyes of his father, Max Rose, as well as recall his younger years growing up in Jacksonville.

Rose, 92, has collected postcards produced in the early 1900s of Springfield and downtown Jacksonville that he has enlarged and framed. Some of the postcards were ones his father bought in 1918 and wrote to mail to his mother, Bessie, who was living in Baltimore before his parents married. He also buys postcards of old scenes in Jacksonville.

He collects postage stamps, too. He remembers digging for stamps in the dumpsters behind the downtown U.S. Post Office building.

Rose’s father was born in Lithuania. His grandfather moved to South Africa to avoid serving in the military, and his father went to live with him when he was 13 years old. Rose’s father and grandfather moved to Jacksonville in 1911 so that his father’s aunt, Ida Feldman, could help raise his father.

“My aunt was extremely wealthy,” Rose said. “In the 1900s, she and her husband, Morris Feldman, owned a lot of downtown Jacksonville property on Bay Street.”

When the aunt died, she left the house that used to be at Post and King in Riverside to Rose’s father. She left the rest of her money to River Garden Nursing Home, Jacksonville Jewish Center and the country of Palestine.

In January 1917, Rose’s father married Bessie Isaacs. In 1919, he opened a grocery store in Springfield at 6th and Market. A Feb. 2, 1935 ad for Rose’s Grocery & Meat Market, at the corner of Sixth and Market streets listed meat prices of 20 cents per pound for homemade pan pork sausage, 15 cents per pound for rump or chuck beef roast and three cans of dog food for 25 cents.

“My father would try to talk guys out of buying cigarettes by telling them that they weren’t good for them,” he said. “He told them that they weren’t made for smoking; they were made for selling.”

William’s father, Max Rose, operated the grocery and meat market for 50 years. In a story that appeared in the Oct. 23, 1972 edition of the Jacksonville Journal, Rose’s father, who was then 81, recalled the early days of operating the store. “In those days you knew everyone, and everyone was your friend,” he said.

Rose’s father had a delivery service as well. “I’d pedal over on a special bicycle with a big basket up front. People would call up for kerosene, and I’d go over, pick up their empty 5-gallon can, fill it and ride back to their house. I made a 10-cent profit on the deal.”

When William was born in 1926, his family lived in the house behind the grocery store. Rose had two older sisters, Mildred Rose Rothstein and Charlotte Rose Fialkow.

“They tell me that my father was so happy to have a son that he added “and Son” to the “Rose’s Grocery Store sign when I was born,” Rose said. “But he took that off before I was old enough to notice it.”

Rose remembers that the streetcar in Springfield used to cost a nickel for one ticket or a dime for three tickets. Cabs cost 10 cents to ride, but they didn’t go everywhere. He had a girlfriend who attended Lee High School. After he finished a school day at Andrew Jackson High School, he would pay 10 cents to take a cab to downtown Jacksonville, and then he had to pay another 10 cents to take a different cab to Lee High School in Riverside.

Rose claims to have visited all of the movie theaters in downtown Jacksonville as well as the Riverside Theater, now called Sun-Ray Cinema, in 5 Points. That theater opened in 1927 and was the first theater in Florida equipped to show talking pictures and had air conditioning.

“I went to many movies at The Florida Theatre,” he said. “I remember Jimmy Knight playing the Mighty Wurlitzer organ in the mid- to late-1930s. The Florida Theatre, built in 1927, was the largest movie palace in Jacksonville and one of only four remaining grand movie palaces of the era in the state.

“I also remember going to the Capitol Theatre on Main Street between 7th and 8th Streets,” Rose said. “My father would give me a dime for the movie and a penny for the gum-ball machine.”

One Saturday in 1934 or 1935, when Rose was eight or nine, he went to the theatre to see what he recalls as “Little Orphan Annie.” When he finally got to the front of the line, he placed a coin on the counter. The cashier said, “Son, the movie is a dime, and this is a penny.” He suddenly realized that he must have put the dime in the gum-ball machine by mistake. “I never did see the movie,” he said.

Rose’s father bought a Pontiac in 1937 from Claude Nolan. “It cost more than $900. I couldn’t believe that it had a radio in it,” he said.

Rose worked for his father in the grocery store until he finished high school and enlisted in the Navy during World War II. He was on the USS Alex Diachenko, which was assigned to the Asiatic-Pacific Theater and participated as a transport ship in the consolidation and capture of the Southern Philippines and Borneo operations.

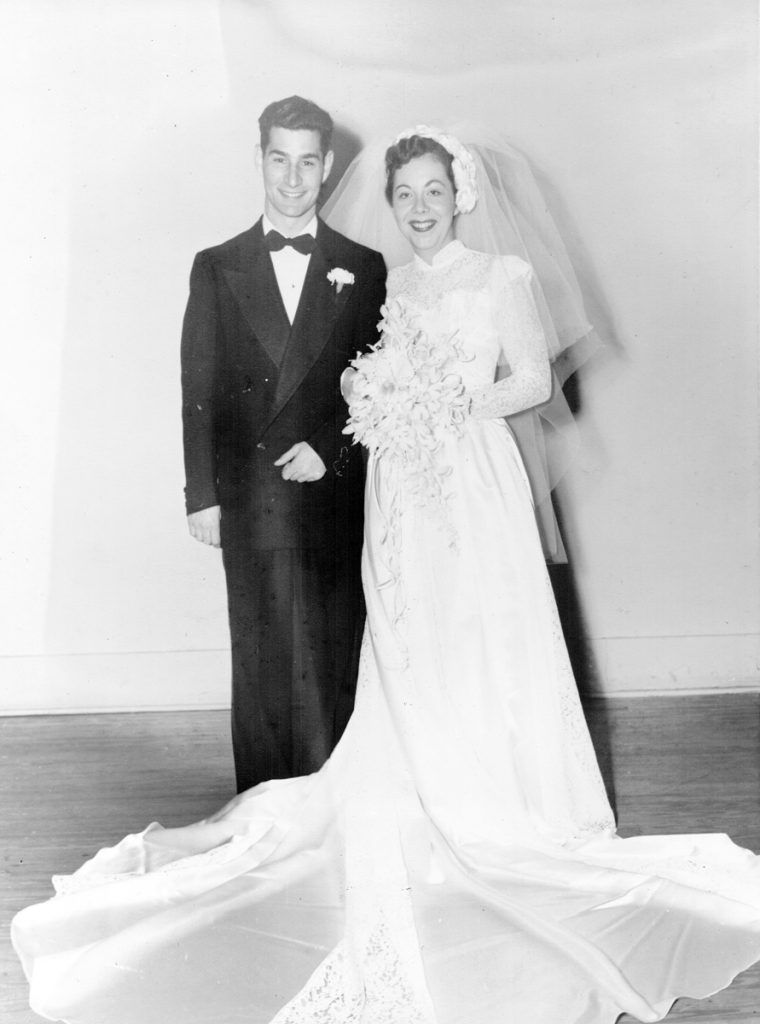

When Rose came back to Jacksonville after service, he lived with his parents for a couple of years until he married Betty Sager in 1951, also a lifelong resident of Jacksonville. She had graduated from Lee High School and Florida State College for Women (FSU).

With his new bride, Rose bought the house he lives in now on San Amaro Road for $17,000. “People wondered why we wanted to live so far out of town,” he recalled.

He used to walk down the middle of San Jose Boulevard because there was so little traffic. “I remember cars hitting the telephone poles because the kerosene street lamps would go out and they couldn’t see the poles in time,” Rose said. “I used my flashlight to help direct traffic.”

He was working at his father’s grocery store in Springfield when he got married, and his daily commute required traveling from Miramar to Springfield every day.

“I’d buy turnip greens from the produce market, take them home, put them in the yard and sprinkle water on them to keep them fresh,” Rose said. “The next day I’d put them back in my car and take them to the grocery store.”

On Dec. 29, 1963, Rose was on his way to work when he saw smoke coming out of all the windows of the Hotel Roosevelt in downtown Jacksonville. Fire had broken out in the ballroom of the 13-story hotel, one of Jacksonville’s most grand hotels, on Adams Street just west of Main. Twenty-two people died, most from asphyxiation and carbon-monoxide poisoning. Some people escaped to the roof and needed help. Rose told the rescue people to call the Navy to get the people off the roof. “The next day I read in the paper that the mayor had called the Navy,” Rose laughed. “But I think they got the idea from me.”

When his father became too old to run the grocery store, Rose sold it. His father told him to go see Benjamin Setzer at National Drug Company, who asked him to come to work for him to oversee distribution. Setzer, a Lithuanian immigrant like his father and a former Springfield resident, had operated Setzer’s Supermarkets that became one of Jacksonville’s early grocery chains by the end of the Great Depression.

Then Rose worked for his brother-in-law’s wholesale grocery, the Hymie Fialkow Company. His brother-in-law eventually sold his grocery to Sysco Corp., where Rose worked as senior marketing associate until his retirement 17 years later.

After he retired, he volunteered in gift shops. He noticed framed stamps that were selling for $25; the stamp was worth 25 cents. He thought would be a good way to get rid of his stamps at flea markets. He also makes kitchen magnets out of postage stamps and has earned the moniker of “The Stamp Man.”

After 30 years of service in the Department of Children & Families, Betty retired and devoted many hours volunteering for her synagogue, the Jacksonville Jewish Center, Hospice and Bikkur Cholim. The couple were married for 57 years before Betty passed away in 2008 and had two daughters, Margaret Rose and Allison Rose Holtz.

Both Betty and William were active in the Jacksonville Jewish Center and the center’s synagogue for many years. Betty volunteered in the office and William made sure the right prayer books were in every one of the 375 seats.

Age has caught up with Rose leading him to decide to quit driving, which means he won’t be going to the flea market any longer. But, he still intends on continuing to frame stamps. “It keeps me busy and I love doing it,” he said.