The Way We Were: Joyce & Malcolm Hanson

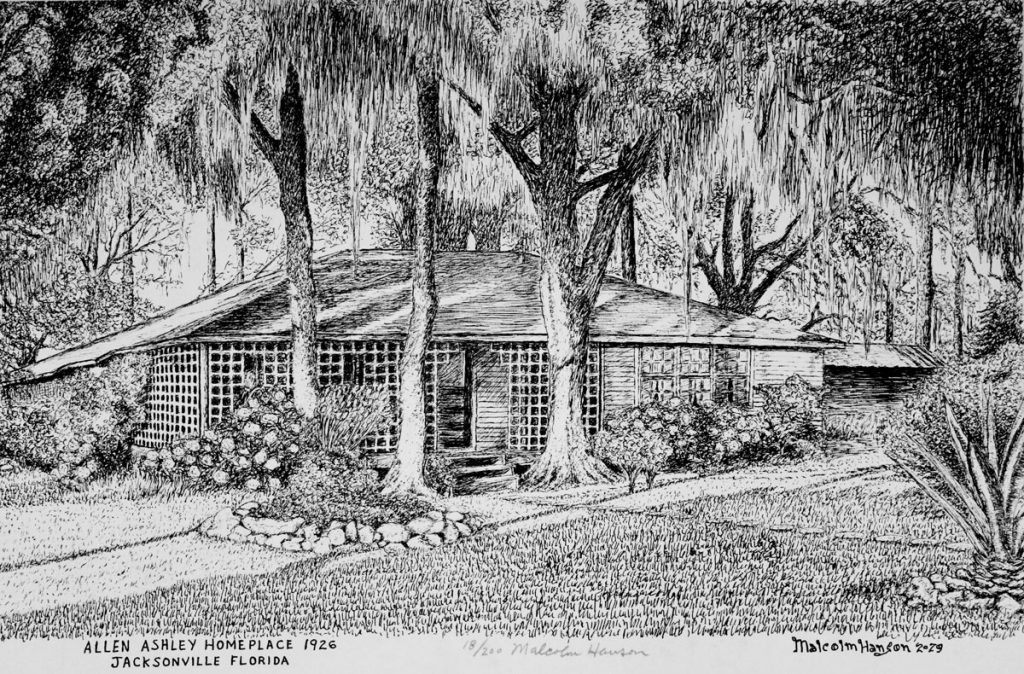

Her most treasured wall hangings in the charming 1942 painted brick home on Dunsford Road help weave the story of Joyce and Malcolm Hanson’s lives individually and together in the San Marco and Lakewood areas. For Joyce, the drawing that hangs just to the right when you walk in the front door captures the beginning of the story. It is of her father’s parents’ home, which was located between Emerson Street and University Boulevard. Joyce’s husband, Malcolm, drew it from an old photo in 1979.

“My dad’s life started in that house,” Joyce said. “I suppose my grandparents would have been considered ‘Florida crackers.’ They lived off the land on a family piece of property with a small garden, and I don’t remember hearing that my grandfather ever worked anywhere else.”

After their four sons were born, including her father, Bob, who was born in 1920, Hanson’s grandparents found the original Ashley home place was too small, and her grandfather, Allen Ashley, moved one section of the house to the side so that he could add a middle section to it in 1926.

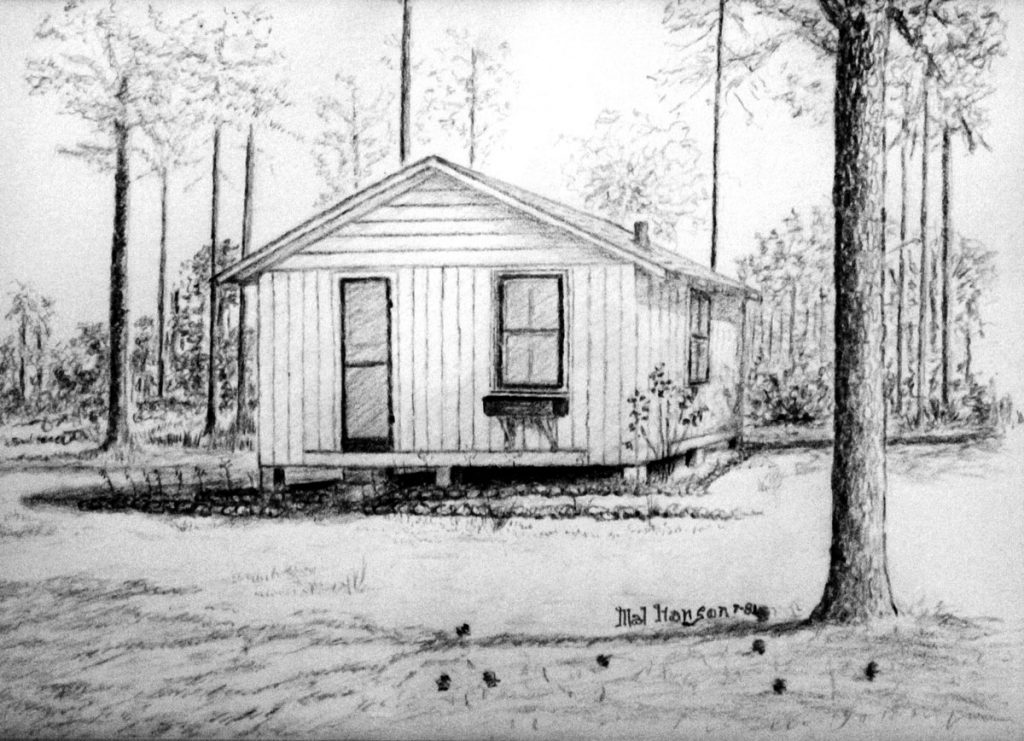

Her grandfather deeded part of the land to her father, who built a one-room house, a drawing of which also hangs in the house. “It didn’t even have a bathroom,” Joyce said. “My parents had to use the bathroom in my grandparents’ house at first.”

When Joyce was born in 1945, her parents added a kitchen, bedroom and bathroom. The house was behind the now-closed Palmer Hall Floors, where Affordable Plumbing is now located. “Our property backed up to a black community with whom we got along,” Joyce said.

Joyce, her brother, Bob Jr., and her parents lived in the small house until she was eight. Then they moved to Rainbow Road into a house her father built in a neighborhood called Fleetwood then, now known as the Lakewood area. Joyce remembers that houses were just beginning to be built in that area.

“We had to go to San Marco to shop at the A&P grocery store in the Square,” Joyce said.

Bob Ashley owned a filling station, aptly named Ashley’s Texaco Gas Station, at the corner of University and St. Augustine where Walgreens is now. “When my dad couldn’t enlist for World War II because of a slight disability, he quit Landon High School before his senior year and went to work in the shipyards,” said Joyce. After the war, Bob installed gas tanks in gas stations for different oil companies and built concrete backyard barbecue pits.

“Because of his dealings with Texaco in helping to build the company’s gas stations, when they wanted to open one in San Marco, they asked him to run it,” Joyce recalled.

“It was a true family-run business. I was in the 10th grade when the station opened and did some of the bookkeeping and ran the cash register,” said Joyce. “But I never pumped gas because women weren’t supposed to! I do now, though.” Her brother, Bob, worked at the station, too, and her mother, Betty, also worked in the office.

“My father became a legend. He loved people and people loved him. He took the time to talk to people. He helped anybody that needed help. He dealt with the least people the same as business executives. He ran charge accounts for a lot of big companies. He was always totally honest in his repairs.”

Joyce remembers the ad slogan, “You can trust your car to the man who wears the star. The big bright Texaco star.” “Every car had the windshield cleaned, the floor swept, the oil checked. People would bring their babies up for him to hold. The station was the hub of the community,” she said.

Joyce went to duPont for first grade and half of second until San Jose Elementary was built and opened. Then she attended San Jose through fifth grade and found herself back at duPont for sixth through twelfth grades. When she eventually taught for a year and a half at San Jose, she was surprised to find that some of the teachers she had were still teaching.

Her parents were married in the little church at the end of Kingsley Road, however, almost all of Joyce’s life is intertwined with the life of Hendricks Avenue Baptist Church, known in the community as HAB. Her parents brought her there when she was three, soon after the church opened. She remembers a little hut in the back to the right side of the gym, the Scout Hut, which was the church nursery. HAB built its first building as a gymnasium, where Joyce was baptized.

“I remember carrying a little flag as we marched to the hymn, ‘Onward Christian Soldiers,’” Joyce said.

Her dad became a deacon at HAB. Both of her parents taught Sunday School classes, and Joyce participated in children’s choir and youth activities.

Bob ran the station from 1960 until he died unexpectedly in 1971, after which Betty and Bob, Jr., ran the station briefly before selling it.

After Bob’s death, Betty donated stain glass windows to Hendricks Avenue Baptist Church in remembrance of her husband. When the sanctuary was destroyed by fire in 2007, the only plaque that could be salvaged was the Resurrection Plaque for her father’s window. A wall hanging of that window and the rescued Resurrection Plaque hang in Joyce’s and Malcolm’s living room.

“Through all of the things that have happened – good or bad – our church has stood with us,” Joyce said. “When my dad died, it was unexpected. My mom fell apart. I was just 24 years old and didn’t know what you did for a funeral. Rev. Lipscomb [Clyde B. Lipscomb, HAB’s pastor then], helped us make the arrangements; without him it would have never gotten done. Everything in our lives happens surrounded by church. That’s why HAB has become our family and support group.”

Joyce remembers that kids from school came to their house for parties. Her brother had a hootenanny band. “Drive-in theaters were wonderful memories. We went until we were teenagers,” she said. “We could wear our pajamas and Momma would bring fried chicken. We did a lot of things as a family and were very close.”

As a teenager, Joyce went to the bowling alley in San Marco, where the AT&T building is now across from Theatre Jacksonville. Malcolm set pins there as a child. “There was a Texas barbecue on San Marco Boulevard,” she said.

I loved the football games at duPont, not so much for the game as for the marching band,” Joyce said. “At one point it was the best in the nation.”

After Joyce graduated from duPont High in 1963, she went to Stetson University and got a degree in education. At the beginning of her first year of teaching at San Jose Elementary, she met Malcolm.

Malcolm was born in New York, but his parents moved to Jacksonville when he was a year old. He lived in apartments in the San Marco area and a garage apartment on River Road while he attended Southside Grammar School. Then his family moved to Belmont Terrace and he attended Landon High School. After high school, his family moved to Arlington and he went to Jacksonville University.

On the day he graduated from JU, a good friend of Joyce’s introduced Malcolm to Joyce at HAB. “We were good friends first, and then we started dating,” Joyce said.

Joyce and Malcolm were married in Rev. Lipscomb’s house in front of the fireplace on Aug. 21, 1967. They didn’t want to have a big wedding because Malcolm was on leave from the military.

While Malcolm went on a military cruise, Joyce continued teaching until Malcolm was transferred to Norfolk, Virginia, for 2-1/2 years, where Joyce taught for half of a year in a public military school until she got pregnant in 1971 and wasn’t allowed to teach any more.

After they returned to Jacksonville, Joyce and Malcolm returned to HAB. Malcolm became a deacon first, and Joyce eventually did as well. “HAB is a moderate Baptist church that didn’t see any reason why women shouldn’t be deacons, too,” Joyce said. Malcolm and she were in the church’s first couples’ class.

When their daughter, Jennifer, was in second grade, Joyce went back to teaching full-time, teaching “hospital homebound” in Jacksonville until 2010, when she retired. “I loved home-schooling because it wasn’t like teaching third grade a hundred times. I taught special needs kids. The sad part was that a lot didn’t survive, but you knew you were providing normalcy. I felt that was my calling,” Joyce said.

Also in 1980, Joyce and Malcolm bought the “Balfour House,” as it is known in the neighborhood, from Betty Balfour Marks, artist, dancer, choreographer and director of her own dance school, the Ballet Arts Centre, and performing company, the Florida Dance Theatre, in Jacksonville. Her husband, Lewis Marks, developed the neighborhood.

When they first saw the house on Dunsford Road, off Hendricks Avenue, it was painted with white trim and a red roof. “I hated it,” Joyce admitted. But then they went inside and saw the hardwood floors and the dining room chandelier, and she had second thoughts. It was more than they could afford so they started negotiating.

“Betty told us that maybe she could help us out on the price if we’d promise to stay in the house and love it and if we’d have our two girls attend her daughter’s Ballet Arts Centre,” Joyce said. “Well we have stayed in the house and our girls did take ballet, and, in fact, our granddaughters take ballet now, too.”

Joyce thinks they live in the best neighborhood in the world. “We walk everywhere. There’s lots of variety. It is a community within a community. We walk just four miles to San Marco Square and know and talk to everybody. We walk to the library, Theatre Jacksonville and the movies.”

Joyce does not have fond memories of the year 2008. “HAB’s sanctuary burned on Dec. 23, 2007, and then I was diagnosed with cancer in 2008 and my mom died as I started treatments.”

The next day, Christmas Eve, the members had worship in the gym, which didn’t burn in the fire. “At the end of worship, All Saints came in and announced they had lunch for us,” Joyce recalled tearfully.

Other churches helped as well, by loaning them music and choir robes. “I remember that a Jewish young lady and her family bought the church pew bibles. The fire pulled the community into HAB and HAB even further into the community,” Joyce said.

During that time, “our grandson, Hunter Closson, was ready to be baptized so we used Rev. Kyle Reese’s swimming pool,” said Joyce, making his baptism unique among the four grandchildren, Rhianna Casey and Hunter, Shelby and Brooke Closson.

Joyce’s daughters, Elisa Casey and Jennifer Closson, used part of the money they had inherited from their grandmother, Betty, to donate new stained-glass windows in memory of their grandfather, Bob. Malcolm helped design the Fire and Dove windows.

The Hansons love that their friends and they have, in some cases, grown up together and have raised children together. And, they count their blessings that they have grown up with Hendricks Avenue Baptist Church and that the church has enmeshed itself in their community.