San Marco author learns about life through care of disabled son

Posted on July 5, 2019 By Editor Neighborhood News, San Jose, San Marco, St. Nicholas

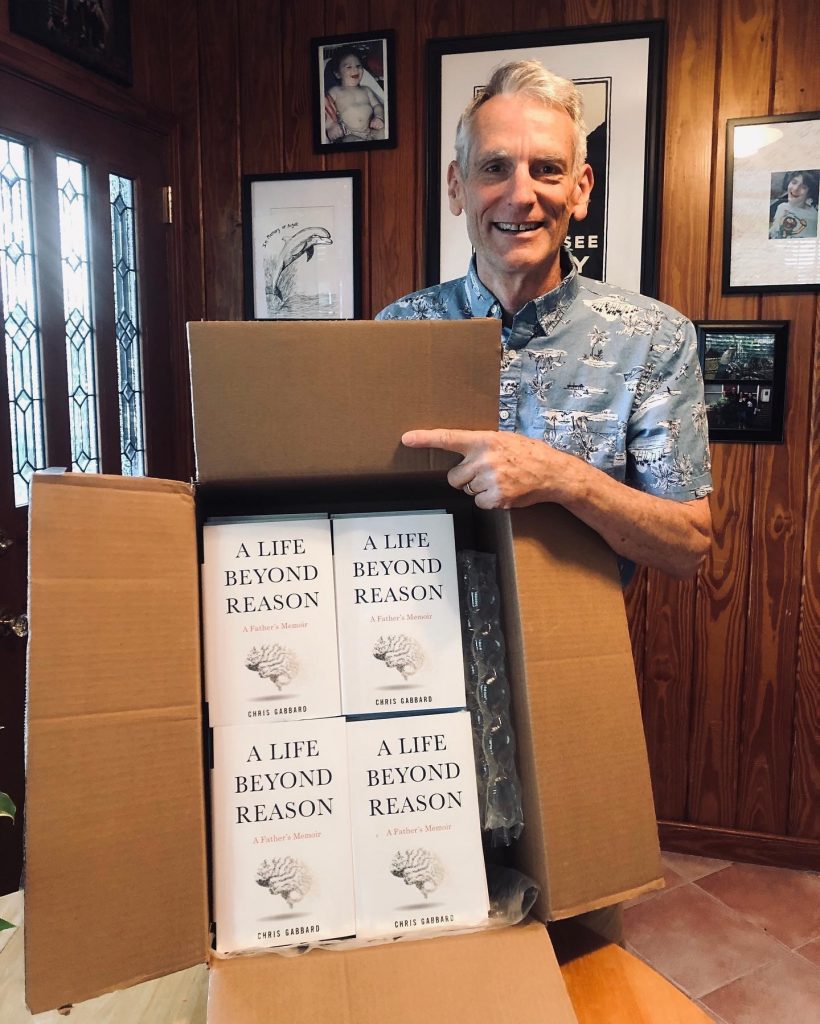

The life that Chris Gabbard shared in his new book, “A Life Beyond Reason: A Father’s Memoir,” would seem like a nightmare to most people. Yet within his memoir, the Colonial Manor resident goes beyond a feel-good story about how to make lemonade if life hands you lemons. Instead he recounts how, by diligently caring for his cognitively impaired, physically disabled son, he was able to learn to the real meaning of love, replacing his life’s ambitions and his strong belief that an “unexamined life is not worth living” with the understanding that his son was a person deserving of life.

An associate professor of English at the University of North Florida, Gabbard, has lived the San Marco area since 2001. After his son, August, died at the age of 14, he spent more than four years writing his memoir about their life together and the insights his family learned from caring for him. His book, recently published by Beacon Press of Boston, may be of special interest to residents in the San Marco area, many of whom often spotted August as he stood upright in a gate-trainer in front of his home on Old San Jose Boulevard.

Although most may not have known August intimately, more than 100 in the community attended his 2013 memorial service, which was held under a tent in the front yard of Joe and Suzanne Honeycutt’s home near the Duck Pond, next door to the Gabbard residence. Gabbard will read excerpts of his work at a book-signing event held at San Marco Books on Wednesday, July 11 at 6:30 p.m.

Life took a dramatic left turn for Gabbard and his wife, Ilene, in 1999, when August was born at a high-end San Francisco teaching hospital and medical mistakes were made. “His was a botched birth,” Gabbard said, noting “all signs were normal” up until August was born. The outcome was a boy inflicted with brain damage (Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy) who was forced to live as a spastic quadriplegic – a person immobile and unable to crawl or hold himself up in a chair without being strapped in. August was also cortically blind, and so severely impaired he had the cognitive abilities of a three-month old, unable to speak, feed or dress himself, or to go without wearing a diaper for his entire life. In fact, August might still be alive and 20 years old today if, in 2010, he had not had complications from an implanted device inserted in his body with the purpose of reducing his spasticity, Gabbard said.

Prior to August’s birth, Gabbard had been an academic on the fast track, having earned his Ph.D. at Stanford University. At that time, he was a disciple of Enlightenment thinkers with a firm belief in reason and the reliability of science. “I used to think if you can’t examine your life, then your life is not worth living, but now I say it’s the life without love that is not worth living,” Gabbard said. Life after August was born became especially hard, not only because of his son’s condition, but also because a California law made it impossible for Gabbard and his wife to sue for malpractice. The Gabbard family, which two years later included daughter Cleo, struggled financially after moving to Florida because it took several years for August to obtain a Medicaid waiver from the state to assist with his humongous medical bills.

The transition from feeling that caring for August was ball-and-chain to loving life with him was not instantaneous, Gabbard said. “If I were a younger man, and you told me this was my future, I would have run screaming, torn my hair out, and said there is no way I’m going to do that. The rational thing would have been to smother him with a pillow. That’s why the book is called “A Life Without Reason.” That was something I had to think about. If I was a reasonable person, I would have smothered him, and nobody would have known the difference because he was so impaired. But I didn’t want to smother him. He gave me too much joy. He made me think, as a professor, about what makes us human and whose life is worth living,” he said. “I had wanted to be a great scholar with my publishing and my teaching when I got my Ph.D., but I realized that couldn’t happen because of August. The time demands were too great. Then I had an epiphany. I decided to become a great dad instead.”

Gabbard said he learned many things by caring for August including patience and how to let go of life’s ambitions. “You have to be patient when you take care of someone like this because you have to be his hands and feet,” he said. Caring for him “slowed down time, so you felt like you were living in a different time zone,” he said. “You have to learn to be patient or you will tear your hair out and all you can do is seethe with anger, but I was never angry with August because I always felt I was on his side. The things that happened to him were not his fault. He didn’t cause this to happen. He was the victim of these things happening to him. I always felt like he and I were a team.”

Explaining August’s medical problems and his family’s legal difficulties trying to receive compensation from the medical community that caused his condition are sub-themes of the book but not the main one. “My real reason for writing this book was that I wanted to tell of the joy of living with him and my experience being with him,” Gabbard said. “He was a delightful little creature, even though he couldn’t see, and he could hardly move. He laughed a lot and was a very joyful, jolly little fellow. He was quite a delight to be with, and I never felt when I was taking care of him that it was pointless,” he explained.

“The book is dedicated to Harriet McBryde Johnson, who said, in the context of a New York Time’s article, that taking care of a disabled child can be a beautiful thing. I remember when I first read that saying ‘What?’ but soon after, I said to myself, ‘I’m going to make this a beautiful thing. I’m going to make this into a work of art.”

By Marcia Hodgson, Resident Community News

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)A Life Beyond Reason: A Father’s Memoir, August Gabbard, Chris Gabbard, University of North Florida