The Way We Were: Ken Juro

Even though he was not born when his father fought the Japanese during World War II, Ken Juro learned plenty about resilience and conscientiousness from his father’s tales about his wartime experience.

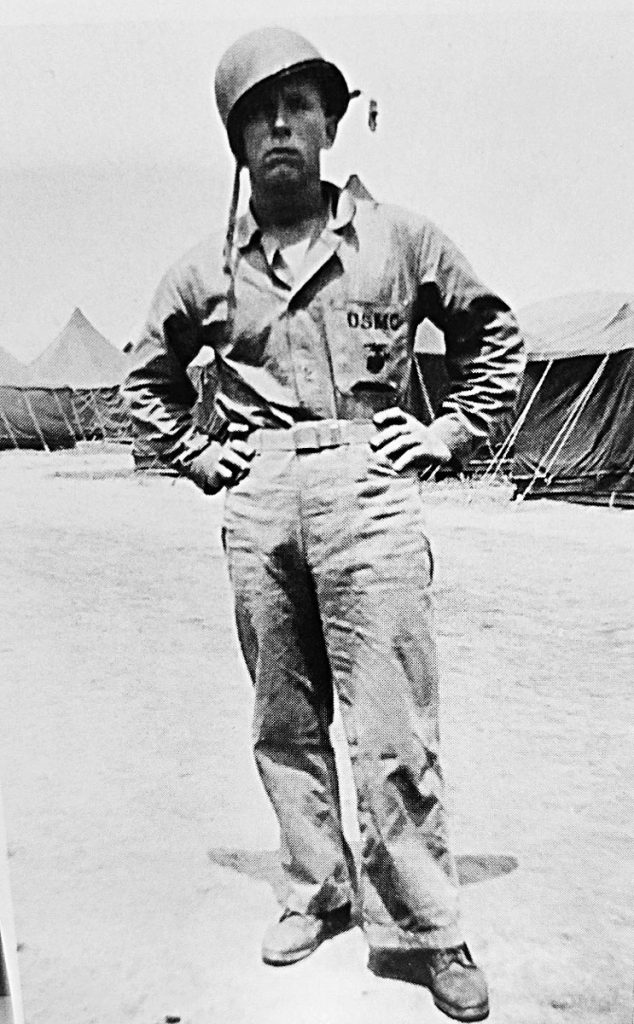

Juro, an Empire Point resident who has longtime ties to Ortega, grew up in Spring Park in the 1950s and often worked in the Ortega business his mother co-founded, Rahaim’s Walls and Floors. He is also the son of war hero Leo Juro, who, through his strong faith in God, survived horrible torture in Japanese death camps as well as the Bataan Death March, which killed thousands of soldiers.

The Bataan Death March, a deadly, arduous march in 1942, in which thousands of U.S. soldiers were either marched to their deaths, died from exhaustion, or were killed with bayonets, took place on the main Philippine island of Luzon after the U.S. surrendered the Bataan Peninsula to the Japanese on April 9, 1942, according to the U.S. Department of Defense. During the ordeal, approximately 75,000 Filipino and American troops were forced to make the 65-mile march to prison camps, where many were later tortured and/or killed. When Juro’s father came back to the States after surviving the camps as a prisoner of war, he weighed only 61 pounds, Juro said. It took the elder Juro more than a year to recover.

In 1939, Leo and his friends were in New Mexico and were excited to assist the war effort when they enlisted in the U.S. Army, Juro said. Leo was serving in the Philippines when the Japanese bombed the archipelago on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after they bombed Pearl Harbor. That attack began the invasion of the Philippines, and Leo fought in Luzon and was trapped and captured by the Japanese after the U.S. surrendered the islands in 1942.

It’s hard to say which atrocity was worse – the march or the death camps. His father told him that during the marches, his Japanese captors starved and beat the soldiers and tortured them by day and by night. When they didn’t kill them, they ran bayonets through their legs or through their feet if they fell down. If the soldiers asked them for something to drink, they would be given contaminated water or rice that would eat away through their intestines before they died.

“Daddy said soldiers used to find maggots in the streams, and they would hold them up on their hands and suck on them to get nourishment because the Japanese wouldn’t feed them food or anything. All the rations the Red Cross sent over there, they used for their own soldiers. They didn’t give the prisoners any of the antibiotics or anything,” Juro recalled.

Leo was in several prisoner of war camps in the Philippines and in Japan including Camp O’Donnell, Nielsen Field, Cabanataun, Formosa, Nokahama, and Osaka, with the worst being Camp O’Donnell, which was located on Luzon in a former U.S. military base.

“In the camps, it was terrible, totally inhumane,” Juro recalled his father saying. “All the waterboarding, all the torturing. Think of the worst thing you can and what was done to those men was probably worse,” he said.

Juro said his father and the other soldiers kept their sanity by prayer. The men would pray and chant the Hail Mary and Our Father prayers. “All the men who would pray would chant while they were being tortured,” he said.

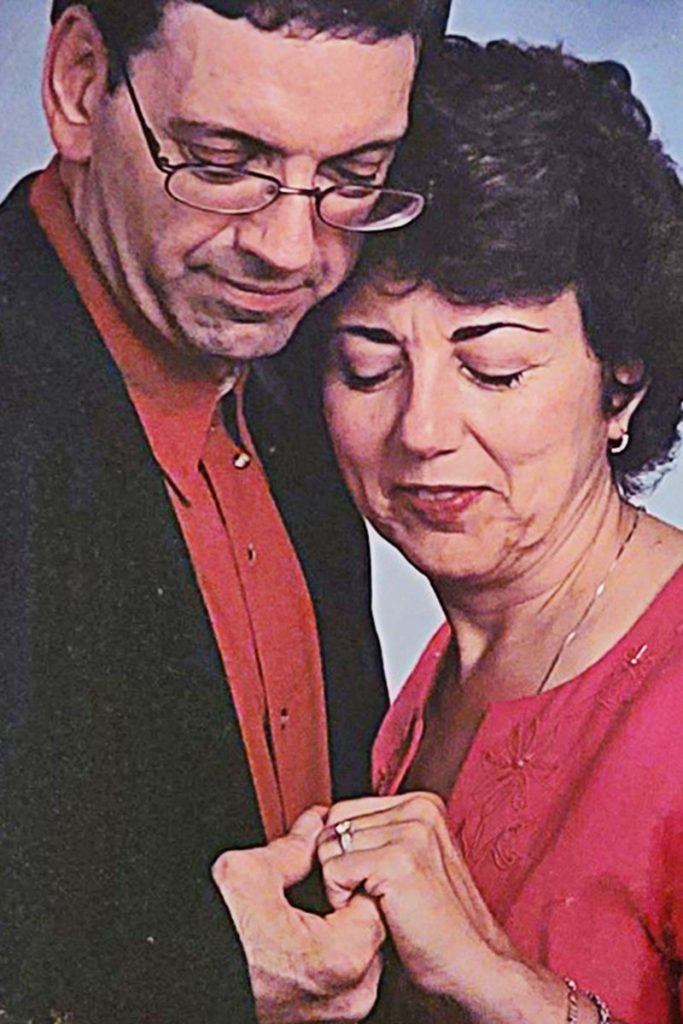

His father was in the Nokahama camp when he was liberated. Health care workers and nurses on converted hospital ships found the soldiers in railroad cars and in caves. Leo returned to San Francisco and began a long, slow recovery from malnutrition, beriberi, malaria, and other illnesses. He later moved to New York, where he met and married Juro’s mother, Marie. They eventually moved to Jacksonville, where their sons were born. Juro later petitioned to get the medals his father had earned, but Leo Juro wanted no part of it.

“I’ve asked my father a hundred million times for a picture of him in uniform. He said there was nothing,” Ken recalled, noting his father had objected when he asked former United States Representatives Corrine Brown and Ander Crenshaw for help in obtaining his medals. But his father was proud to meet, and be acknowledged by, Ret. Lt. Col. Oliver North when he was undergoing dialysis at the VA clinic in Gainesville in the late 80s.

Before he died on Aug. 3, 2004 at the age of 88, Leo Juro finally had possession of his medals but never wanted anyone to see them, particularly his family – his brother-in-law, and sisters, Juro said. “I used to take them wherever we would go because I was so proud. When we held his funeral at Assumption Catholic Church, I didn’t bring his medals because Dad always said it was old news and he didn’t want anybody to know.” However, Father Dan Shashy stopped the service and waited as Juro went home to get them.

“I brought them, and he put them on the casket then proceeded with the funeral. Dad also received a 21-gun salute.”

Although his father’s war tales were often grisly and graphic, Juro said he learned lessons of resilience and conscientiousness that have helped him throughout his life, especially his father’s emphasis on the importance of faith within the family.

“Buddhism had been shoved down his throat in the war camps, but he was a stanch Roman Catholic. When we all went to college and we would get on the phone, he would say ‘what’s the Gospel about today?’

“He gave me damn good roots,” Juro continued. “He never, never was upset with the Japanese after what they did to him. I had friends who would refuse to go to an Asian restaurant because of what he went through. But he would say, ‘they have good food, they are good people. They need to make money like the rest of us. You just have to trust in God and your fellow man. That’s what you do.’”

Born in Jacksonville, Ken Juro, who still runs Rahaim’s, grew up on the cusp of Jacksonville’s historic districts and recalls going to the Rexall-type drugstore counter, which served breakfast and dinner, and shopping for baseball cards nearby. He also fondly remembers working and spending time in Rahaim’s Walls and Floors, his mother and relatives’ Ortega wallpaper and interior store.

“Ortega has always been quaint,” he said. “It was just so laid-back, like where we were raised in Spring Park. In Ortega, you had the rich people and they were rich and had a pool, but that didn’t matter. They used to have the little ice cream shops where they would sell ice cream cones for 25 or 35 cents, and you could get a double-dipped cone. They also had the little grocery stores, the Mom-and-Pop stores. Those can’t be replaced. I love Riverside and Ortega. A lot of my customers are from the Ortega Area.”

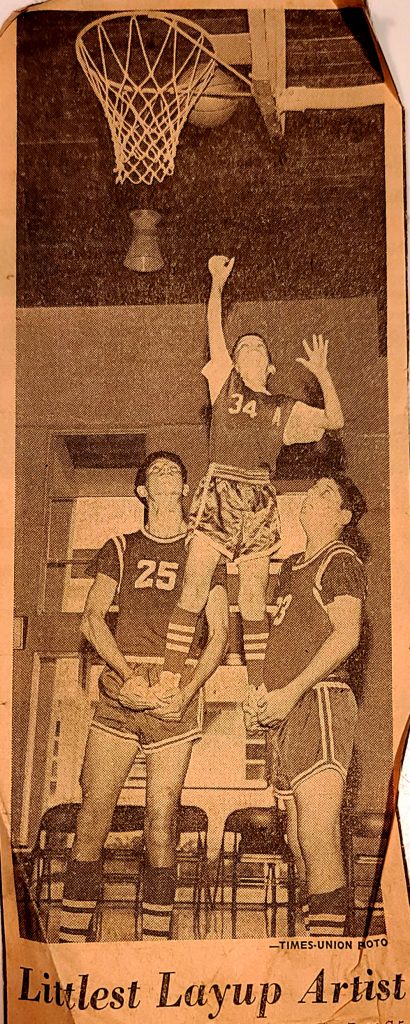

Juro and his younger brother, Greg, attended Assumption Catholic School and Bishop Kenny with the financial help of extended family. His father volunteered as a Bishop Kenny basketball coach and his mother, Marie, sold concessions at the games, which were bought with her own money. Juro graduated from high school in 1969.

“It was so nice back then,” Juro recalled. “Everybody knew everybody. I played ball, my brother played ball, and we didn’t have a car until I was 12 years old. Back then, to go to Bishop Kenny was $25 a kid. Assumption was $10.50. My daddy worked at the post office until 2 or 3 in the morning and he would walk home.”

Juro recalled the time when he grew up as a time when everyone kept their doors opened and unlocked. He would tend to the 40 or 50 drink machines in the area and work at the post office during the holidays. No one had air conditioning and Skinners’ Diary trucks drove around to people’s homes to deliver milk. Everybody seemed to know his father wherever he went, and he always seemed to run into people he had served with in the military.

“Everywhere we go, we run into someone who knew him. It’s amazing.”

Juro said his father’s war stories helped strengthen him and imparted within him the importance of work.

After his ordeal, his father turned to faith instead of medicine to survive and taught his children to turn away from resentment. Juro recalled as he was growing up, his father would flush medication and sleeping pills down the toilet and tell him he found more peace by going to the church sanctuary.

“Back then, life was so easy and so neat, and everybody knew everybody, especially when there were rotary phones,” he said. “The operator would know who you were and who your family was. She would ask how your mom was,” he remembered.

Leo Juro’s father, Ken’s grandfather, emigrated from Yugoslavia to Montana, where he worked as a coal miner. Leo Juro shortened the family’s last name from Jurovich to Juro, and when Juro once asked his father why he did not change his name back to Jurovich, a task that would only cost $25 at the time, his reply would be “Why should I spend money on something like that?”

But, his father also taught him generosity and the need to help his fellow man.

“Dad would help anybody,” he added. “If he saw people Downtown begging for money, he would give them money. He used to irk my mother to death. He would be parked on the side of the road, giving $3 or $4 dollars. He was just that good.”

By Jennifer Edwards

Resident Community News