In Memoriam: Ann Carrell Jeter

November 16, 1916 to July 17, 2020

If athleticism, wanderlust, and humor can keep a person young, then it’s no wonder Ann Carrell Jeter lived more than a century. The Riverside native made it to 103 before she died in the early morning on July 17 due to complications from COVID-19 and pneumonia. One week before her death, Jeter spoke to Mary Wanser of Resident Community News in a phone interview.

It was November 16, 1916 when she was born at home on the corner of St. Johns Avenue and Cherry Street. “I was in a hurry,” she said, adding that her mom had no time to get to the fairly new Riverside Hospital, the birthplace of Pat Boone in the 30s and Jeter’s first child in the 40s,

“I’m a full Floridian!” she announced with pride. Her mother was born in Gainesville, her father in St. Augustine, and a grandmother near Fernandina—where Jeter used to visit the sugar cane fields as a little girl.

At four years old, Jeter started school. She had seen her older brother going, and she insisted that she wanted to go, too. “Back then, they didn’t pay any attention to formal records. You could just tell them anything. I guess I mumbled,” she admitted. Looking back, Jeter realized it was too young. “It’s better to be a little older than a little younger,” she said, due to differences in maturity levels.

Their family’s first car was a Studebaker, purchased when Jeter was near six years old. On most Sundays, as a treat, the family would go for drives and stop for peanuts and ice cream cones. Ten years later, Jeter would learn to drive the Studebaker, and a Sunday treat as a teen would be driving with a date to Imeson Airport, sitting on the car fender, and watching the planes come in. “It was really exciting because they didn’t come very often!” she said.

Her family sold their Riverside home and moved to Springfield because Dr. Francis Miller, Jeter’s uncle, had been living with them. He was head of the surgical department at Old St. Luke’s Hospital on 8th Street, and a streetcar ride to get to the hospital from St. Johns Avenue took entirely too long.

The folks who purchased the Carrells’ home, the Barwalds, eventually transported the two-story house from Riverside to Mandarin by river barge. This was the same family who began Barwald Landscaping and the Flying Dragon Citrus Nursery, both iconic Jacksonville businesses.

Jeter said her mother was not happy about the move to Springfield because her sister lived in Ortega, and that was too far away. So, the family moved back to Riverside and lived on the corner of Talbot Avenue and Herschel Street for a long time. “Those were happy years. That’s when I was going to Lee,” Jeter said. She enjoyed walking to school only a few blocks away and “picking up people as we went along.”

Jeter had begun high school at Andrew Jackson but then transferred to Robert E. Lee when her family moved back to Riverside. She graduated from there at 16 years of age. After high school, she took a few post graduate courses during the Great Depression but did not have a formal college education. “I’ve always read a great deal, and I feel like I know almost as much as someone who went to college,” she said.

Sports was the only hobby Jeter ever had, with a single exception. “I spent one summer making a yo-yo quilt,” she said with a laugh as she shared the intricacies of cutting cotton cloth and threading edges into rosettes. Jeter admitted she never did stitch all the panels together. Her mother had, for many years, saved the pieces that never actually formed a completed quilt. She then learned to knit, but she always returned to her beloved basketball.

She liked all sports and played all she possibly could, but her first love was playing basketball on the city playgrounds and on an independent team that won the Florida state championship. The rules back then were different from today’s modern game and had been modified from the men’s game because it was generally thought that basketball was too rigorous a sport for women.

When she was older, but still young and single, Jeter lived out on Jacksonville Beach for a year in the late 1930s. She remembered the boardwalk area being very rustic. She played Bingo there using corn kernels as markers. She had ridden the huge, wooden roller coaster twice. “I was so frightened. I thought I was going to die then,” she admitted, noting the experience took place 81 years ago.

Jacksonville changed greatly over the decades, particularly the downtown area, she said. There used to be three major department stores—Cohen’s, Levy’s, and Furchgott’s—and there was more formality when people went shopping. To shop or eat lunch at the original Green Derby on Adams Street or at Jones Drug Store at the corner of North Main and East Bay Streets, a woman would dress in high heels, hat, gloves, and matching purse, she said, and the big hotels hadn’t yet turned residential. “It was very chic to be seen at the Carling Hotel,” Jeter said, noting it was a popular dinner and dancing venue, more popular than even the Hotel George Washington. And downtown Jacksonville was safer. “I loved the Seminole Club and the restaurant down in its basement!” Jeter also recounted how, after shopping, ladies could leave their packages unattended in the restroom there and go out to buy more. “Nobody would bother them,” she claimed.

As Jeter remembered it, Mrs. Estes, the woman who ran that basement restaurant at the Seminole Club, made a famous devil’s food cake and her daughter, Bunny, married Nicky duPont in 1937. “That was quite the social event of the year,” Jeter recalled. The bride was carried on a pile of palm leaves into the reception held on the duPont estate, which is now Epping Forest Yacht and Country Club.

Jeter’s first job, which paid five dollars per week, was at a one-room insurance company in the old Cohen’s building downtown. After a month, when she grew tired of answering phones, she worked at Stockton, Whatley, Davin Real Estate. There, she began dating Joe Davin, the vice president, who one night had to cancel their dinner plans to meet with a client. To not let her down, Davin had his native Virginian housemate, Bill Jeter, accompany her instead. From then on, “I had dinner with Bill every night for the rest of his life,” she said. She had stayed at the company for a year or so but quit immediately after their wedding in 1941. She said her new husband was stunned when she left her job. “I worked for him, but I’m yours forever,” she told him.

Jeter was 24 when the couple built a home in Mandarin. “It was two dirt ruts in the woods. That’s all it was. And now, it’s a metropolis,” she said. Her husband had paneled every room with pine, which she personally hated, but “I liked it because he liked it,” she said. They had a very happy life there.

Bill practiced law as representative for the Gulf Life Insurance Company and then, after the company was sold, as independent counsel for many years. They raised four children. As her daughters tell it, Jeter’s dream was to give birth to five boys so that she could have her own basketball team. When her first two children were born female, she gave them male names, Shannon and Payson, still hoping for that team. When her third was a boy, named William after his father but dubbed Crown Prince, Jeter realized a basketball team was not to be had; so, when her fourth and final child was born a girl, she named her Jane.

The Jeters played tennis every Sunday afternoon with a group of six others. From the court, they’d go down to the water and gather shrimp to cook and eat for supper on the dock. They won a lot of local team tournaments at the San Jose Country Club. In later years, a friend taught Jeter to play golf. “Never with my husband. I was afraid he would have beaten me,” she said.

Jeter was always an active participant in Jacksonville society. She joined the Garden Club when there were only 31 members, and she was part of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America.

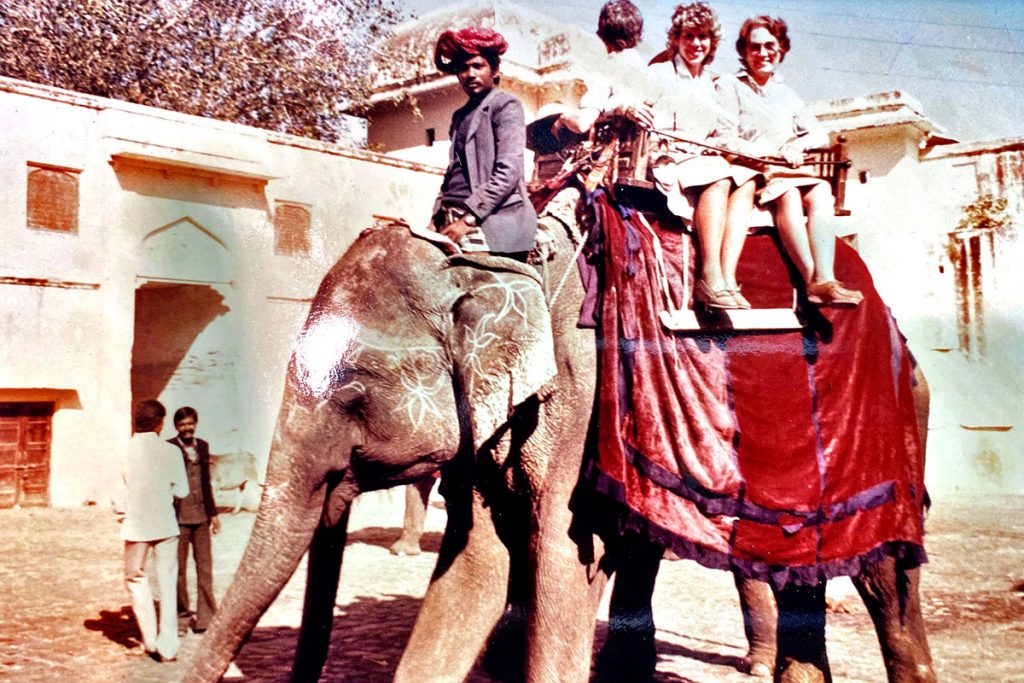

Jeter also traveled the world. “I’ve gone almost everywhere I wanted to go,” she said with satisfaction. “It’s the most wonderful education you can get. You learn more from a trip than you do from a book.” She visited most of Europe; Egypt and Kenya in Africa; Thailand and India in Asia; and that’s not all. Some countries she visited two or three times.

Jeter spent time travelling by sea. She and her husband visited the islands many times on the boat of Margaret and John Lovejoy, a prominent Jacksonville orthopedist. She even cruised the Columbia River to follow the path of Lewis and Clark.

During a trip down the Nile River with her eldest daughter, Shannon, who loves puzzles, Jeter admitted to smacking her hand and admonishing, “Would you please look at the scenery. I didn’t pay all that money for you to do sudoku.” Jeter also smoked hookahs at an outdoor café in Morocco and chewed betel nut in Burma. “It’s supposed to be a narcotic, but it didn’t do anything as far as I was concerned except leave a bad taste in my mouth,” she said.

Even though she was a self-proclaimed “tight wad,” Jeter gambled some. She learned how to place bets at the age of 15 when she visited the dog track in St. Augustine with her father. She could spend $10 in no time at the Dutch Mill when gambling was legal in Florida. She sat in a box seat at the Belmont Stakes in New York. And she attended horse trotting races with carts in California.

For 41 years, Jeter remained in their family’s Mandarin home, long after her husband had died. “I couldn’t stand the woods anymore,” she said, so she traded her house for her son’s Riverside condo across from Memorial Park. “He got the better of that deal,” she said.

Jeter also spent 13 happy years in her 80s and 90s in the two-story, white stucco, elevator-less building on Ortega Boulevard where she could walk to St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, the drug store, and the post office.

When she was 97, Jeter moved into the assisted living facility The Windsor at Ortega when it opened six years ago, and she assembled its library. “I was younger, and stronger, and healthier, and I moved every book in there,” she said. Bilingual, she also attempted to start a Spanish class, but no other residents were interested.

Before her death, she began compiling sayings into a book of sage advice, which she intended to give her children. When asked what advice she’d offer to today’s world, she shared: Keep your eyes open and your mouth shut! “Everybody talks too much,” she said, and added her most beloved line from one of her favorite books The Rubáyát of Omar Khayyám written by a Persian poet. “The moving finger writes, and having writ, moves on. And neither your piety nor your wit can erase a single word of it.”

Kate Riggs, sales director of The Windsor, said Jeter was a frequent winner in trivia contests, even when competing with 15 other residents. Jeter was humble and bragged not about herself but about the intelligence of her neighbors. Jeter won prizes such as toilet tissue, rolls of paper towels, and Hershey bars, which she gave as Christmas presents to family members for fun.

Because the rest of her family had died in their 80s, Jeter guessed the secret to her longevity was her interest in sports. “I was a lot more athletic than any of them were. Sports was what I lived for,” she said. “I never dreamed I would live to be this old,” she said just a week before her death.

(14 votes, average: 4.79 out of 5)

(14 votes, average: 4.79 out of 5)