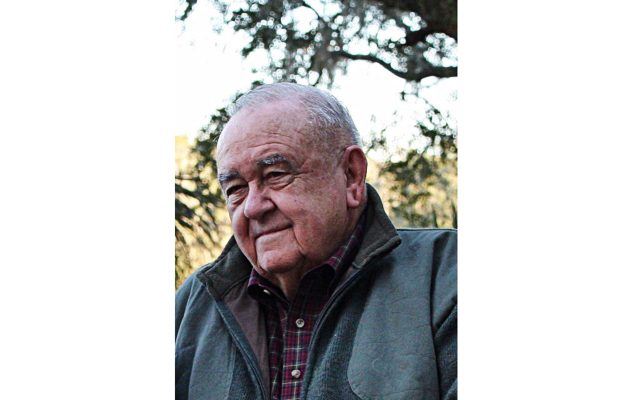

In Memoriam: Arthur Chester Skinner, Jr.

February 20, 1922 to August 7, 2020

Philanthropist Arthur Chester Skinner, Jr., who played a major role in the development of Jacksonville’s southside, passed away peacefully in his sleep of natural causes Aug. 7.

Referring often to himself as a simple “country farmer,” the always humble Skinner was so much more than that. Throughout his 98 years, he was first a family man who relished raising his children and giving back to his community. During his life he worked as an engineer, operated a successful dairy business, served on multiple community boards, gave abundantly to his alma mater, The Bolles School, and generously contributed to the growth and expansion of his hometown, Jacksonville, which he dearly loved.

Born on February 20, 1922, Skinner grew up in South Jacksonville at a time when the lands to the south and east of the St. Johns River were mostly woods, marsh, or sand dunes.

Skinner’s family had ties to Northeast Florida for more than a century. His father, Arthur Chester Skinner, Sr., built the first house on Old Kings Road South, when Old St. Augustine Road was still made of brick and University and San Jose Boulevards were dirt roads.

In 1926, when Skinner was 4 years old, his parents attended the grand opening of the San Jose Hotel, which is now the main building on Bolles’ San Jose campus, said John Trainer, Skinner’s longtime friend. Skinner often shared with Trainer his vivid memory of theevening. “It was a major opening, black tie, on New Year’s Eve. Mr. Skinner remembered that his parents were getting dressed up to go, and his father complained to his mother that he really didn’t want to put on a tuxedo,” Trainer said.

It was just a few years later after the elegant San Jose Hotel went bust that the building was transformed into the headquarters of Bolles, a military school. Skinner’s father, who ran a dairy, signed his son up and paid for his tuition by supplying the school with milk, said Trainer. At Bolles, Skinner excelled in both athletics and academics, graduating in 1940 as class valedictorian, class president, battalion commander, and honor cadet, all achievements he rarely, if ever, mentioned to his family. “We didn’t even know he was valedictorian until we walked into Bolles Hall and saw his picture hanging on the wall,” said his daughter, Kathy Skinner Newton. “He never told us. We had no idea at all. He was very humble.”

Upon graduating from Bolles, Skinner continued his education at Georgia Institute of Technology, where he competed in basketball, baseball, track, wrestling, and football, playing as a lineman for the Yellow Jackets in the 1943 Cotton Bowl against Texas. Earning a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering in three years, he was again named valedictorian of his class. Years later, in 1999, Georgia Tech inducted him into its Engineering Hall of Fame.

Throughout his life, Skinner credited his education at Bolles and Georgia Tech with opening his eyes to a whole new world for which he was very grateful. “Bolles did a lot for me with a prodigious education, introducing me to the military and great athletics,” Skinner told The Resident in April 2020. “It truly was the beginning of my awareness of the world and all its opportunities.”

A member of Georgia Tech’s ROTC program while in college, Skinner joined the U.S. Army immediately after graduation and was sent to Fort Monroe to serve in a coastal artillery unit where he was trained in the new field of radar technology. There he led the charge of making design modifications, testing, and assembling super-secret radar units, as well as training personnel. After six years of Army service, he was discharged at the rank of second lieutenant.

Upon returning to Jacksonville, Skinner took a job with Reynolds, Smith and Hills, a local engineering and architectural firm before joining his brother, Charles Brightman Skinner, in forming Meadowbrook Farms, a wholesale and retail dairy company. After selling the business in 1985, Skinner successfully committed his time to several family-owned enterprises – farming and cattle, timber operations, real estate, and investments. At that time, he was instrumental in the planning and donation of family lands for the University of North Florida campus, J. Turner Butler Boulevard, Interstate 295, St. Luke’s Hospital, and the A.C. Skinner Memorial Youth Baseball Complex, which was named in honor of his late father.

Skinner also served the Jacksonville community as a director of American National Bank and a founding director of Memorial Hospital. But perhaps closest to his heart was The Bolles School, which he supported generously both as a trustee and ardent champion of its athletic programs.

“No single individual has done more for the Bolles community throughout its history than A. Chester Skinner Jr.,” said Bolles President and Head of School Tyler Hodges. “His commitment to the school began during Bolles’ earliest years when he led his peers as class president and valedictorian and continued unwaveringly through the decades through innumerable volunteer positions, campus projects and work in all areas of school life. Mr. Skinner tackled projects with the goal of strengthening and improving our programs and kept a keen eye on the campus needs until his passing at age 98. He has enriched our school in many ways, and always did so with determination, commitment, and humility. Our community has lost a great man, alumnus and friend.”

Skinner was a life-long member of Riverside Park United Methodist Church, which was where he met his wife of 45 years, Katherine Godfrey, who died in 1996. The couple had four children. He later married Constance Stone, who was also a member of Riverside Park UMC. His four children, Arthur Chester “Chip” Skinner III, Katherine Skinner Newton, David Godfrey Skinner, and Christopher Forrest Skinner as well as his 15 grandchildren and 27 great grandchildren all attended Bolles.

And while he was a frequent spectator at Bolles plays, recitals, and sporting events, he was a football fan first, and a close friend of Coach Corky Rogers, said Trainer, former Bolles head of school. “My wife, Alice, and I would sit with him at football games. Most of the time our team would be pretty far ahead, and I would say, ‘Mr. Skinner, are we feeling sorry for the other team yet?’ He would say, ‘no, not yet.’ Often, we would get accused of running up the score, which Corky opposed. Corky would put in his second string, then third string, and on occasion we would still be running up the score and I would ask, ‘Mr. Skinner, are we feeling sorry for the other team yet?’ He would say, ‘no, not yet, but we’re getting close,’” Trainer recalled.

“He was one of the most enjoyable people I’ve ever had the privilege of working with. He was amazing, optimistic, and always supported and encouraged others. He was a great patriot and loved our country,” Trainer continued, adding that Skinner was responsible for installing flagpoles in the front and rear of Bolles Hall as well as ensuring that the school’s Skinner-Barco football stadium was built to his specifications.

A man who enjoyed working with his hands, Skinner very talented in carpentry, constructing benches and other additions to the Bolles’ stadium in his backyard workshop. He also crafted five children’s playhouses, all in different architectural styles, for the families each of his children and a niece, where he personally designed and drew the plans, said his daughter, Kathy, noting her Victorian playhouse came complete with a fireplace, a mantle, a ceiling fan, and two working bay windows. “They were beautiful works of art,” she said.

But most important, Skinner was a man filled with humility, the kind of person whose spirit endeared him to everyone he met. “I’d take him to the Mayo Clinic, and he would know the guy who pushed his wheelchair – where his child went to school and who is wife was. He’d know the same of the woman who drew his blood and of the doctor he went to see,” Kathy said, adding he mowed grass and often picked up trash on the Bolles campus. “Somebody once told me when they were Bolles they saw my father was on a stepladder changing a lightbulb and thought he was the custodian,” she said.

“He was very interested in other people. He gave 110% to everything he put his mind to. He always had time for you and made you feel special. He never missed an opportunity to tell you how proud he was of you. I think he had an impact on a lot more people than we realize. Several people have told me that he was like a second father to them,” she continued.

Since her father’s death, Kathy said many people have reached out to her family to share how her father inspired them. “One person shared this: ‘Your dad never told, he showed and calmly expected us to watch, learn, and follow suit. He taught me that no matter your background, no matter your status, set a goal, and work hard. If you are willing to do this, you will earn the respect of those around you.’ I thought that summed up very well who he was,” she said.