Horticulturist saves rare orchid from extinction

Thanks to Houston Snead, a Riverside resident and horticulturist at the Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens (JZG), together with Lisa Hassell, an environmental specialist from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, a rare flowering plant, may be saved from extinction.

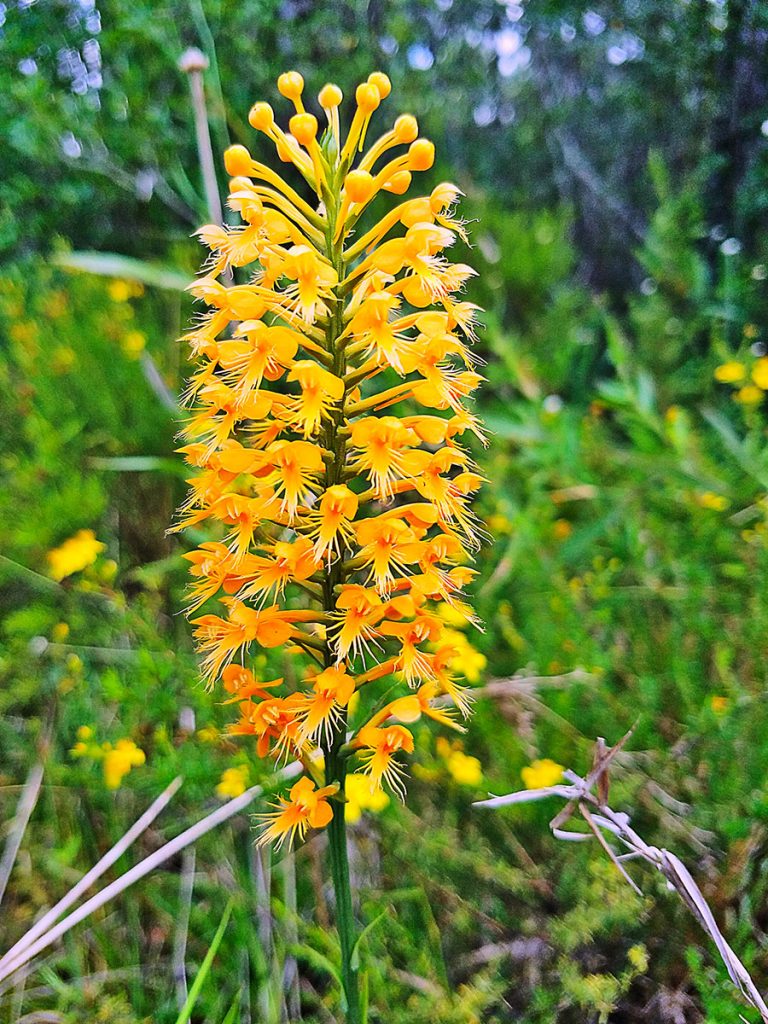

Snead and Hassell did a comprehensive survey in the state of Florida of the Chapman’s Finged Orchid. They determined it to be endangered. But Snead didn’t stop there. He and Hassell went on to petition the Florida Endangered Plant Advisory Council. These actions led to the Chapman’s Fringed Orchid, in October 2017, being designated as endangered in the Florida Regulated Plant Index and, therefore, under legal protection by Florida state law. Snead’s passionate actions continue to help the Zoo conserve the species, which it now maintains a habitat for.

The Chapman’s Fringed Orchid is so rare that it’s found in only three locations in the entire world—all within the United States. Only 15 % of the total population is found in Texas and Georgia, with the remaining 85% in Florida. Snead and his team monitor the orange-colored wonders in the local wild, and they look for new species. “We usually find them along roadside ditches,” Snead said. “There are numerous threats to the plants in these ditches.”

So, Snead works with roadside vegetation managers to halt mowing and spraying and to develop strategies for the plants to persist there, flower, and go to seed. “Some of the seeds are then collected for banking in case a population is lost. We can replace it with a back-up,” Snead explained. “I just didn’t know,” he said is a common refrain. “But once they know, they’re happy to protect the orchids.” Snead said that a global challenge for scientists is to educate without offending.

Those familiar with orchids commonly use the Goldilocks and the Three Bears metaphor. Orchids don’t like it too hot or too cold. They need all facets of their environment to be just right. That’s why the health of all else in the ecosystem can be predicted by the orchids’ flourishing, or lack thereof. “It’s important to safeguard them against extinction,” said Snead. They are nearly extinct due in large part to poachers who scout out the exotic plants in the wild for their own collections. Urban development is another threat. “Comfort comes at a cost,” Snead warned.

“Plants support the animal life,” he explained. Plants supply food, oxygen, and habitat for animals, including humans. “Plants, along with microorganisms, are the backbone of what holds the ecosystem together.” Because microorganisms cannot be seen except through a microscope, plants, particularly those known as keystone species, are the visible “indicators that the rest of the ecosystem is healthy and intact,” Snead said.

So dedicated is to saving plants in Florida that not only do they house the largest public garden in the region but also take one dollar from each entrance ticket sold at the gate plus four dollars from each membership sold and put those funds toward conservation efforts—maintaining their own programs as well as issuing grants to help finance others’ endeavors. The money supports activities such as field conservation projects not only for plants but for animals, too.

“Forming conservation alliances is a trend across the Southeastern United States,” Snead indicated, noting a lack of funds due to “plant blindness” among the general public often hampers funding efforts to save rare plant species. “To get more funding is the number one reason,” he pointed out with regret. “It’s mainly charismatic animals that get attention. Plants are important parts of the ecosystem, too, but with very little funding.” Plants are often viewed as mere decoration rather than the necessary part of life that they are, he said.

A united voice in other states has shown to be effective with this crisis. “So now, since 2016, we have one in Florida,” Snead said. He founded the Florida Plant Conservation Alliance, modeling it after Georgia’s successful alliance. “Ours is still building, and it’s gaining momentum.” The key, he learned from that group, is having a paid, dedicated coordinator. JZG makes this possible, as it’s written into Snead’s employment contract with the Zoo. His job with them includes species and habitat-focused projects; one of those projects is the Alliance.

As local coordinator of the Florida Alliance, Snead works with county agencies, public utility companies, universities, and other botanical gardens. He partners with these federal and state organizations—like the Florida Department of Transportation, for example—pooling their resources to recognize all endangered species in Florida and to attempt protecting and saving native plant populations.

There’s a further concern among plant conservationists. “There’s a labor deficit in the green industry. Many colleges have dropped horticulture programs. The green work force is aging out,” Snead advised. In an effort to attract youth to the field and inform them about green industry jobs, a nationwide nonprofit has formed, Seed Your Future. As Snead is a young man renowned in Florida for his conservation efforts and as a zoo plant keeper, the organization has featured him in a special video that highlights his important work. “I am what I want to be when I grow up,” Snead said, wrapping up the video.

Snead is a local boy who’s “always been surrounded by plants.” He shared that his paternal grandfather belonged to the Jacksonville Garden Club and had a variety of plants growing in his backyard. His maternal grandmother had various collections, too. Following in his father’s footsteps, Snead’s first job while in high school was at a Jacksonville plant nursery.

Born and raised in San Marco, Houston Snead is currently a resident of the 5 Points area of Riverside, where he enjoys bike riding through the urban core when he’s not working in open fields or slogging through swamps.

To view Snead’s video turn to www.seedyourfuture.org/zoological_horticulturist.

By Mary Wanser

Resident Community News