Group works on projects to beautify Willowbranch Park

A local community group hopes visitors who come to Willowbranch park this Valentine’s Day share the progress of the park’s transformation and the love for those that died from an illness that afflicts thousands of people in Jacksonville.

At noon, Friday, Feb. 14, members of the Memorial Project of Northeast Florida will celebrate the first anniversary of the founding of Love Grove, one of many improvements that have already begun at the park. A stand of trees will gain 20 more in addition to the ones planted last year to commemorate those who died of HIV/AIDS. Other planned improvements for the coming year include a City-funded reforestation project, a privately funded mural, and a stately and inspiring public work of art that celebrates those that died of the AIDS virus.

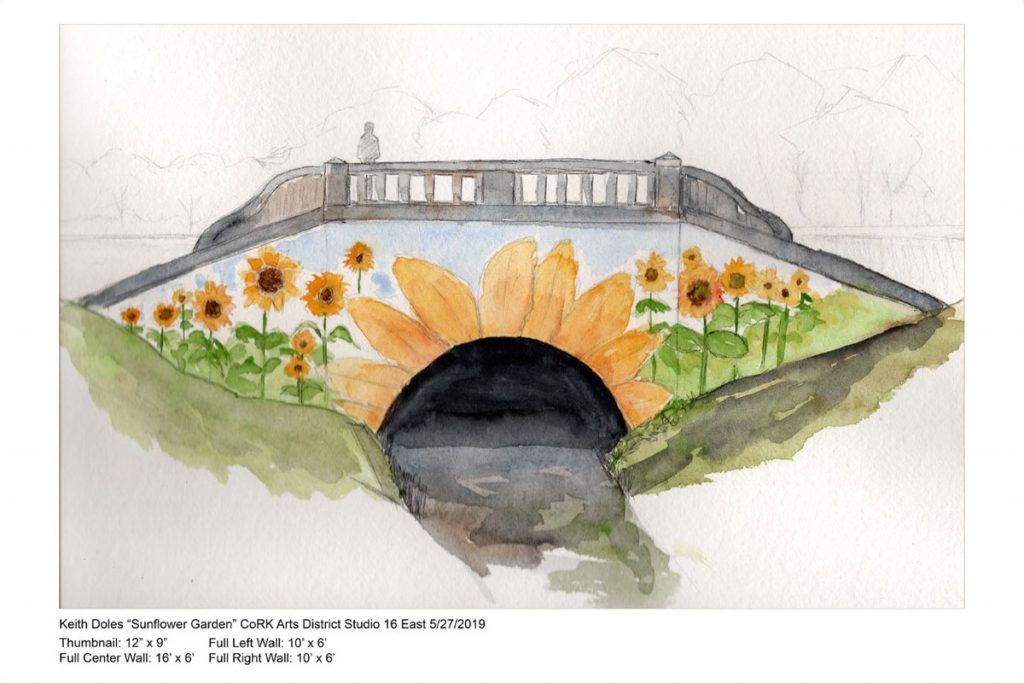

The Riverside park is serene and sheltered by a strong assembly of oaks. The idea for the park was conceived in 1916 by Former City Councilman John J. Griffin and developed in the early 1920s, when it was decorated with 1,700 azalea bushes. Willowbranch Library, which lies next door to the park, opened in 1930. Willowbranch Creek flows the width of the green from Sydney Street to Park Street before slipping under a traffic culvert. Soon, the culvert will blossom with public art, and 100 new trees that will be planted in the park by the City to thicken the canopy. The new trees will share space with Love Grove’s memorial trees, which the group hopes will stretch the length of the channel.

Richard Ceriello, president of the AIDS Memorial Project of Northeast Florida, said a private donor provided the funds for local artist Keith Doles to transform the culvert across the creek with a sunflower mural, and the group hopes Jacksonville will soon harbor what will be the second memorial in the Southeastern United States to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

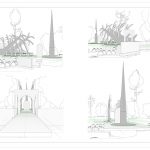

Slated for construction in glass and steel and rife with symbolism, the plans for the memorial also include a spire that stretches 20 feet toward the sky. Architect D. Scott Fraser of Design Development Architecture donated the design work as did local landscape architect Scott Dowman, Ceriello said. Raising enough money for the memorial’s construction – $150,000 to start – will take time. But on Valentine’s Day, the nonprofit Aids Memorial Project of Northeast Florida will be celebrating Love Grove, the first phase of the project, one year after members planted the first trees in memory of their loved ones who died from HIV/AIDS.

LOVE GROVE

The group is accepting donations for more trees to expand the grove, which will be planted along the water in memory of loved ones who lost their lives to the disease. Last year, 10 people read 10 names of loved ones who died, a moving experience for those who participated. Wally Ericks, a group member and point man for the grove, watered the trees every other day. A neighbor across the way lent his hose to help. A small, nondescript bridge now crosses the water feature and the future site of the grove, near the culvert that will bear the mural. Members of the group, which has been incorporated for two years and has a board of directors, want to transform the bridge into the memorial. Currently, the group and the City are collaborating on the final plans. Once the City stamps the project, fundraising will begin in earnest, Ceriello explained.

“We’re dedicated, we are not going anywhere,” he said. “This will only be the second memorial in the Southeast. The other is in Key West.”

The memorial plans, provided at no cost by D. Scott Fraser, an architect with Design Development Architecture, are highly symbolic. Visitors will walk over a yellow brick road inscribed with the names of donors, then into a steel archway flanked on either side by the stylized outlines of falling trees and continue their journey over a glass bridge that represents the journey from life to death. At the other side is a tombstone-shaped portion that will be engraved with the names of those who died. Above, a 20-foot spire is to point to the clouds, conjuring a theme of ascension. A yellow brick road with the names of donors will lead up to the bridge.

“All we need now is an email from the parks department for us to proceed and it’s going to be on,” said Ceriello referring to fundraising.

“This park in a few years is going to look a million times better,” Ericks said with a smile.

‘A PLAGUE’

In 1982 and 1983, a new and virulent plague was burning through the neighborhoods surrounding Willowbranch Park. First, people began dying in singles. Later, people died in scores, leaving almost no neighborhood block unaffected. And those unlucky enough to contract HIV in the days before compassion and treatment attended support groups that grew smaller and smaller with each meeting as members passed away unpredictably. The public was scared, and no one knew how the deadly virus was transmitted, and there was so much rhetoric describing it as “a gay disease” that people who were not gay thought of themselves as immune.

At that time, a diagnosis of HIV didn’t come with just a death sentence – death usually came within six to nine months – but also included excommunication from all the comforts of being human, witnesses of that time said, including community activist Frieda Saraga, who lives in the San Jose area. Families abandoned loved ones who had contracted the disease. Nurses wouldn’t bring their afflicted patients their meals, but rather left them outside the hospital room door. And holy men? Many wouldn’t approach the afflicted, either.

Joe Caliandro, a sturdy and kind-eyed member of the memorial group said he was with a friend dying of the disease and watched as a priest refused to give his friend last rights in person. “He would only do it outside the door,” he said, fighting not to tear up even as a faint wetness escaped. “That’s their job.”

Saraga and Ceriello watched the first waves of HIV decimate the Riverside and Springfield neighborhoods. Saraga and business owner Ceriello said the areas were ground zero for the disease, and they can’t look at all the homes around the park without remembering so many who died. Both say that the disease was characterized as a gay disease, or a drug user disease, even as it affected all segments of the population.

“We have lost a tremendous number of individuals, and women and children, to this disease,” Ceriello said. “At the time, it was highly politicized and (victims) were turned into villains. These were victims of a disease and the disease did not discriminate. It’s been almost four decades now that we have been experiencing this in North Florida. This memorial is to remember these wonderful people who were in the prime of their lives and in most cases, who would have gone on to bigger and greater things and improved our city.” Ceriello lost his partner to the disease. Tony O’Connor was just 33 when he died after a long illness.

Mary Glenn, a 66-year-old Jacksonville Westside resident, said that when she learned of her infection Sept. 14, 1990 – 30 years ago this year – it was hard to believe.

“From what I read in the newspaper I didn’t think it would happen to me. I wasn’t gay, I didn’t sell sex, I was only with one man at a time, I didn’t’ do intravenous drugs. I didn’t think it would happen to me,” she recalled. She took a deep breath before continuing to say, “I remember going to support groups and lots of lots of people dying. They just wouldn’t be there the next week. In the early ’90s, there were a lot of people dying, so many. But after ’95, with the drugs that came out, it changed things – a complete turnaround. So many people are living longer and healthier lives if they choose to by keeping your body helping. No smoking, exercise. You can leave to a ripe old age. I am 66, I will live a normal life cycle – 72, 80, maybe 85.”

Since her diagnosis, she has worked hard to change stereotypes about who gets the disease, and the belief that HIV is an immediate death sentence or means someone affected can’t have a normal life. “We can date, live in neighborhoods, own houses, drive cars, those things that in 1990 I didn’t think were possible, they can still can happen and they do happen and nobody has to know about my HIV unless I tell them,” Glenn said. But she chooses to tell people. She is firmly in support of the memorial. “The project, that is needed here in Jacksonville. There are so many people that have passed on and we need to remember them. The traveling AIDS quilt project is a momentary thing. We need to see something visual that would give and show respect.”

By Jennifer Edwards

Resident Community News

(4 votes, average: 4.25 out of 5)

(4 votes, average: 4.25 out of 5)