The Way We Were: Wayne W. Wood

Many years before Wayne W. Wood, 74, became a noted historian, author, and the founder of Riverside Avondale Preservation, he was just a kid from Belle Glade in South Florida visiting grandparents Guy D. and Elma T. Wood during the summers in Riverside. That was decades before he would run a successful optometry business in Riverside and then go on to transform the area with an artistic mix of intelligence, passion, creativity, and rabble rousing.

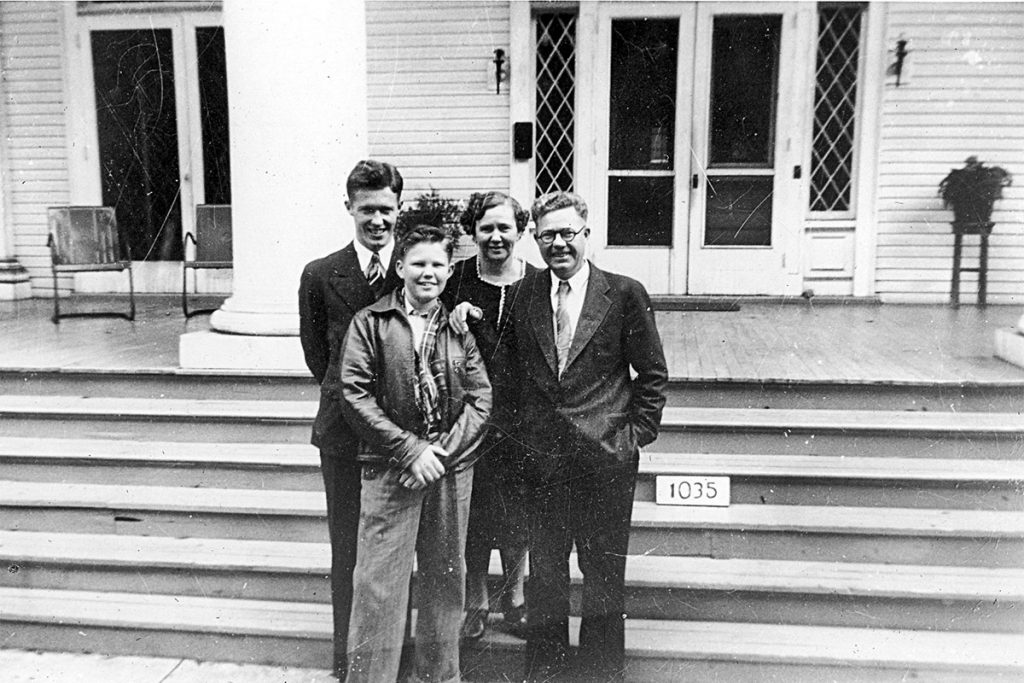

You could stay it started with his grandparents’ expansive home at 1035 Riverside Avenue, one of 50 stunning historic mansions and period homes collectively called “The Row.” The three-story manse on the corner with Bishop Gate Lane was set among beautiful scenery on a lot that backed up to the river where crabs, shrimp and all kinds of fish could be sought and caught at a moment’s notice, and children could walk to City parks and entertainment nearby. Located between Memorial Park and what today is the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens, the home had been initially built as the residence of an important Episcopal Church bishop.

By the 1950s, the bishop was gone, and the home had gone through several owners before Wood’s grandparents bought it. As a youngster visiting with his older brother Darry, and later, his younger sister Rosanne, Wood was deeply impressed with his grandparents’ apparent wealth, although he knows differently now.

“They had this big three-story house, and the white columns on the front were so big that my brother and I couldn’t reach around and touch each other. We thought they were so rich because they had 65 people for dinner!” he remembered, smiling. It turned out, they weren’t wealthy; they operated a boarding house and often barely made the mortgage. However, the boarding house would house generations of people and entertain him and his brother for years.

“When I got to visit, I got to stay in this great big old house, and often I would get to stay up on the third floor, and it was kind of mysterious up there. It was great in the summertime because they had vacation Bible school over at Riverside Methodist Church, where my grandparents were staunch members. Down the other way was a children’s museum, where (Jacksonville’s Museum of Science and History) got its start. My brother and I would always go over there, and they had a stuffed buffalo in the lobby, crazy stuff.”

What would later be called “the Woodshed” would go on to shelter hundreds of people, including young people who liked to fish with Wood at the bulkhead at the end of the lot or shine lights to spot running shrimp and enfold them in cast nets. The lot extended all the way to the river.

At the time Wood was visiting, the mansion was past its prime, he realizes now, but to his younger self, it was impressive, and the neighborhood where it was located, wondrous. And, his summers there would spark the reverence for history and historic homes that led him to found Riverside Avondale Preservation, an organization that has saved or preserved hundreds of structures and helped shape the integrity or what is now a defined historic district.

In the Weed’s

The Episcopal Diocese of Florida built Wood’s grandparent’s home for its third bishop, the Rt. Rev. Edwin Garner Weed, in the early 1900s. Wood said it was built around 1910. After Weed, it went through several owners by the time the Woods bought it in the early 1930s in the Depression. Wood’s grandparents bought it for $9,000 with a mortgage, which equals about $135,000 in today’s dollars according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. At that time, they could barely afford the mortgage, and the large house required a tremendous amount of upkeep, including salaried housekeepers. To this day, Wood can’t recall them painting it once in 40 years. A house like that required its owners to be wealthy and wealthy people lived elsewhere by that time, he explained.

“It was called the Woodshed. It was beloved,” he recalled. “It became famous because thousands of people lived there when they were growing up, getting out of school, when they were in the military or had a job, and so all these young people lived there and they went on and got married,” he explained. “My grandmother counted over 100 people who lived there that she helped get married. She was a matchmaker. When I came to Jacksonville and started my optometry practice (with his uncle Dr. William H. “Bill” Wood) in 1971, it seemed like every other day a new patient would come in and say, ‘I lived with your grandparents in the Woodshed.’”

Wood described his grandparents as wonderful people.

“They both grew up in Georgia. My grandfather grew up in Valdosta and my grandmother grew up in Dixon,” he reminisced. “They were just good, old, salt-of-the-earth people, they grew up in good Southern families.” His grandparents had two sons, Wood’s father, Guy D. Wood Jr., and his uncle, Bill, who was just 10 years older than Wayne, and an optometrist who inspired Wayne to follow in his footsteps.

“Bill started a practice in 1950, and then I graduated from optometry school in 1971, and it was only natural that I came to Jacksonville and took over the practice with my Uncle Bill. My father was in the produce business in South Florida, and he forbade me from going into that business, nor did I want to. Everybody liked my Uncle Bill. He was a teenager and he grew up in that boarding house surrounded by dozens and dozens of young women staying in that house.

“He must have had a terrible time,” he joked, laughing.

From “The Row” to RAP

Wood graduated from Emory University in 1967 with a degree in English but soon realized he needed to learn something else. “I wanted to be a writer and an artist but in my senior year I realized I wasn’t very good at either of those things and I would always be working for someone else.” He attended Houston College of Optometry and graduated in 1971, thinking, “I’ll never be rich, and I’ll never be poor, but I’ll at least be able to be a writer and an artist and not be very good.”

He joined his Uncle Bill’s practice, which operated on the fifth floor of the Exchange Building, 218 W. Adams Street. The two would go on to work well together, except for what Wood called “one problem.”

“He liked to hunt, and I was a tree-hugging environmentalist. He knew that if he had me come (join him) there would be someone to cover the entirety of hunting season. We grew the practice and I retired 10 years ago.” That was after they moved their office to 1500 Riverside Avenue, at the corner of Riverside and Lomax, to a building that was later torn down.

During the early years of his practice, Wood noticed a disturbing trend: All of those striking, historic homes, the 50 called “the Row” and built after the Great Fire of 1901, were being torn down at a tremendous pace in the 1970s, the victims of both neglect and the encroachment of what was then St. Vincent’s Hospital, which was expanding quickly in the area. There was no one to pay the enormous cost of upkeep for the homes, and the hospital had plenty of money to buy and demolish them.

The Woodshed was not spared.

“(My grandparents), they were just like adoptive parents for hundreds and hundreds of people. Eventually, when they got too old to run the boarding house, they moved to a little bungalow out in Ortega,” he said. “My uncle, who was handling their business at the time, arranged for a restaurant to come (to the Woodshed), La Maison, which means the Mansion. It was a wonderful restaurant, a fancy, French gourmet restaurant. It had fancy wallpaper. The restaurant didn’t make it. The food was wonderful, and the people loved it. But because they were close to the church three blocks away, they could not get a liquor license. Then they turned it into a cooking school, and they had a fire in there.” They tore it down and built a small insurance building, which is still there today.

“The fire was the last nail in the coffin,” he continued. “A big house like that, you need a lot of helpers: cooks and maids and yard people. There was an old African American couple behind there, that did the cooking and cleaning. By the time it got torn down, it was seven years before RAP got started. If (RAP) had been there, it would have gotten saved. It was in the wrong part of the cycle. There are only two houses out of the 50 that are still left, on the corner of Riverside and Lancaster. One is a bed and breakfast, the Riverdale Inn, and the other is a doctor’s office.”

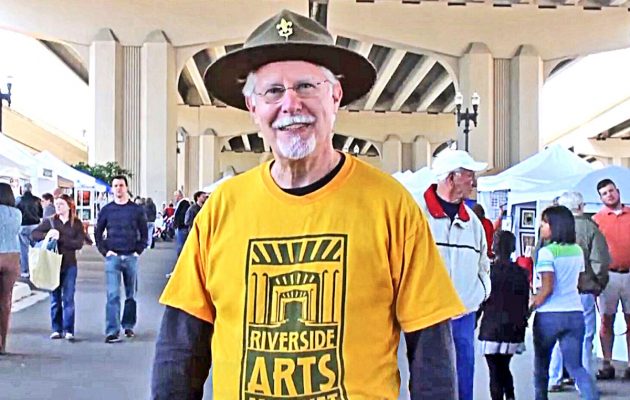

It was all this destruction of history, including the Woodshed, that led Wood and three other like-minded individuals to found Riverside Avondale Preservation. Wood has been at the forefront of neighborhood preservation efforts ever since, writing 13 books about Jacksonville and its history. He is the founder and is a board member of Friends of Hemming Park, where his wife Lana Shuttleworth Wood, an acclaimed traffic-cone artist, lent her 8-foot-tall, arresting piece: “Origins: The Giant Chicken,” just in time for One Spark. He also cofounded the Riverside Arts Market, which takes place under the Fuller-Warren bridge and now attracts more than 4,000 visitors each Saturday, according to the RAP homepage.

Wood said it was only natural for him to come back to Riverside after graduating from optometry school, even though his grandparents’ house was gone. There is a silver lining, however; he and Lana live in a home built right around the same time. Built in 1913, it became a hospital in the 1940s, when staff there built what Wood called “an abominable addition” that the Jacksonville Symphony tore down when it bought the home in 1976. Wood has lived there many years and decorating it lovingly with an assemblage of all kinds of art, including a 66-inch-by-60-inch oil-on-canvas wedding portrait of him and Lana by local artist Jeff Whipple.

Wood said that he loved growing up in Belle Glade in Palm Beach County but did not want to go back there. Multiple sources report that the town has continued to experience decline, poverty, and high criminal conviction rates. Wood said its vitality is gone.

“To this day, it is not some place I am especially fond of. It was a wonderful place to grow up, but it has died and is not a place many people would want to go to,” he related.

Fortunately, Riverside-Avondale has so far been spared the same fate, thanks in large part to Wood with his community activism and leadership of RAP. Now, in the 21st century, the area has gotten the kind of nods the area got near the beginning of the 20th century.

In fact, in 2010, The American Planning Association recognized the neighborhood. “(Nearly four decades after urban blight) Riverside Avondale is more than just a neighborhood; it’s a destination for thousands who attend its weekly arts market, stroll along the riverbank, shop and dine in one of its quaint commercial corridors, relax in its parks, or attend worship services at one of its historic churches,” it wrote on its website.

“Nobody can remember how horrible it was,” Wood said. “This was a neighborhood that was truly dying.”

Today, Wood takes note – with satisfaction – of the progress that Riverside and Avondale have made. “The great parks we have, just the design of the neighborhood. You have little Mom and Pop shopping centers … you can talk to the person who owns the shop. You have schools and museums … it’s a rich neighborhood,” he said.

By Jennifer Edwards

Resident Community News