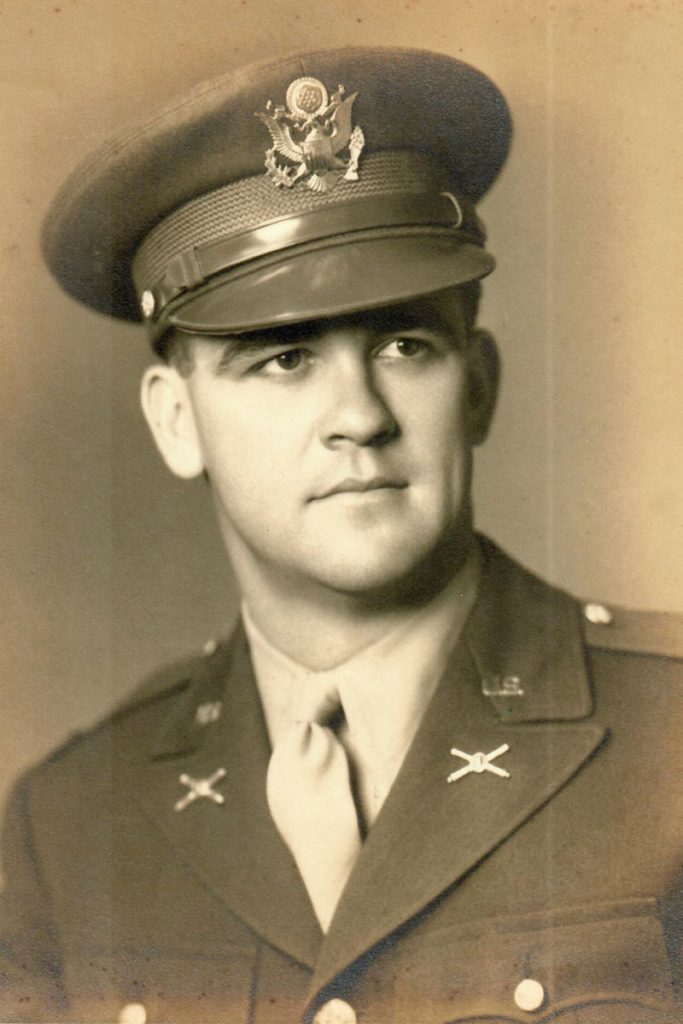

The Way We Were: Arthur Chester Skinner, Jr.

As the sun’s rays penetrated through the pine trees, a young man galloped down the dirt roads of a primitive South Jacksonville in the 1930s on his horse, Vinny, long before commercial and residential areas and the city and state roads needed to provide transportation to them, were developed. This was when the lands south and east of the St. Johns River were mostly woods, marsh or sand dunes; before Southside subdivisions, Southpoint, Deerwood or University of North Florida existed, or Southside and Beach boulevards, Phillips Highway and State Road 220, for that matter.

Yet this young man, Arthur Chester Skinner, Jr., and family generations before him, would play a major role in the creation of what we now know as Jacksonville’s Southside, all because of the Skinner family’s hard work, vision and generosity.

“The Skinner’s are originally from South Carolina and my dad and several uncles ended up in Jacksonville due to my grandfather’s continuing quest to acquire more virgin lands for his timber and turpentine business in the late 1800’s,” explained Skinner. Timber was the mainstay of family patriarch, Richard Green Skinner’s naval store business, and he was able to find enough financial backing to acquire an empire of pine trees along the St. Johns River – estimated to be more than 40,000 acres – all the way to the Intracoastal. When Skinner’s grandparents unexpectedly passed away in the early 1900’s from pneumonia, the responsibility for the family business and the landholdings fell to the seven sons, one of which was his dad, still a teenager himself, who eventually settled in Jacksonville.

When Skinner was a kid, there were two Jacksonville’s, north and south, divided by the river. “As a child, we would ride a ferry back and forth to cross the river where the Main Street Bridge is now, although it was called the John T. Alsop, Jr. Bridge, after the mayor,” Skinner said. (Actually, it’s the second bridge built in Jacksonville and is the oldest bridge still standing in its original form.)

Skinner’s father built his family’s wood-frame home as the first house on Old Kings Road South, when Old St Augustine Road, running in front of their home, was brick and San Jose and University boulevards were dirt roads. Years later, Skinner’s father would rebuild a brick house on the same spot, and when Chester grew and married, he also built a brick house next door to his father’s.

Skinner’s main passions throughout his 89 years have been his family, football, The Bolles School, and creating opportunities to be a good community steward. When he was a kid, The Bolles School was a hotel, and in 1933 was converted into a boy’s military school serving grades 7 through 12. During the Great Depression, the timber and real estate businesses slowed down. To survive, Chester’s father turned to selling milk by starting and operating a dairy, named Meadowbrook Farms. He got some pointers from their first cousins who were already operating Skinner’s Dairy near Downtown.

Skinner, who humbly still refers to himself as a country boy from the woods, was able to attend The Bolles School during its military era in exchange for his dad supplying milk for the entire school for his tuition. He credits his education at Bolles, and then at Georgia Institute of Technology, as opening up a whole new world for him for which he is grateful. Over the years he has shown his appreciation through a multitude of monetary donations as well as his time and talent. Skinner played several sports both at Bolles and Georgia Tech including football as a guard, basketball as a point guard, baseball as a right fielder, track and wrestling. He graduated from Bolles in 1940, as class battalion commander, president, valedictorian and an honor cadet.

“Bolles did a lot for me with a prodigious education, introducing me to the military and great athletics,” said Skinner. “It truly was the beginning of my awareness of the world and all its opportunities.”

When he graduated with high honors from Georgia Tech with a degree in mechanical engineering, he was technically a part of the U.S. Army being in ROTC, and with World War II still two years out before ending, Skinner was immediately sent to Fort Monroe as part of the U.S. Army’s coastal artillery unit. He was trained to be a radar technician back when this was something new, installing and testing radar equipment along the coast of the Chesapeake Bay.

“Here they formed convoys of ships going to Europe to fight and so we all witnessed so many amazing things,” said Skinner. “We’d go to bed at night and the coast would be jammed full of ships, wake up the next morning and they’re all gone headed to Germany or Great Britain.”

He got to serve with other friends from Georgia Tech, like best friend Harold Achey, originally from Chattanooga, Tenn., who was assigned to the motor transport division. They continued to be life-long friends visiting each other’s hometowns. Achey even named his first son after Chester. After six years of service, Skinner retired from the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant.

He joined Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc., downtown, as an engineer where he designed and coordinated various construction projects including local power plants, such as the one on Talleyrand Avenue, and electric generating stations all over the state. He got to know various other engineers and influencers, such as John Lanahan, when they both worked on getting the Matthews Bridge built, which played a role in future development of Skinner land holdings.

Skinner is very proud of the role the former and current generation of his family has contributed to development, economic success and quality of life that is southside Jacksonville. “My dad and brothers gave away a lot of land for highways to the city and state to open up the land, increase its value and make new developments possible,” he said. “My brother, sister and I cleared and gave the state right of way for so many major highways here such I-295, J. Turner Butler and Southside boulevards, and donated a large portion of acreage where the University of North Florida is today.”

After Skinner had been with RS&H for a few years, his dad wanted to concentrate more on real estate and asked his two sons to take over running Meadowbrook Farms. Skinner would ride Vinny or his shiny, black Model A Ford down mostly dirt roads to the dairy farm, located on the corner of St. Augustine and Old Kings roads, before it was eventually moved to where the Town Center is now. Chester and brother, Brightman, managed the dairy farm and accompanying stores for more than 30 years into the 1970s.

“Brother was in charge of the milking operation while I took care of daily maintenance like fixing fences and keeping water troths full,” said Skinner. The company bottled and sold retail milk delivered by truck to homes and supermarkets in Jacksonville, St. Augustine, Daytona, Palatka and New Smyrna Beach. The San Jose land associated with Meadowbrook Farms dairy became known as Skinner’s Pasture.

By the late 1970s, after the dairy was sold, Skinner focused more on managing his large acreage holdings with a vast amount of tasks such as overseeing maintenance, digging canals for water drainage, meeting with road development people or folks wanting to buy land. He worked from an office he built behind his home.

He had married Katherine Godfrey and they had four children, his namesake, A. Chester, III or “Chip,” as well as David, Christopher, and Kathy. Eventually, parts of Skinner’s Pasture would become the grounds of Wolfson High School, the Dupont YMCA, various residential areas and Baker/Skinner Park, among others. In the 1980s, the land was passed down to his son’s generation. After his wife, Katherine, passed away in 1996, he became friends with a widower at his church, Constance Stone, and they married in 2002.

All the while, Skinner has stayed close to both of his alma maters, especially during football season. In the early days, he helped coach the Bolles Bulldogs and has supported the team and all its coaches over-the-years. His desire to help, along with a love of designing and building, has resulted handcrafted stone benches and wooden banquet tables around Bolles Hall, and players’ benches on the football field all, which were made by Skinner in his backyard. He was also instrumental in the many campus statues memorializing Bolles’ military history, commemorative flagpoles, tree plantings, and school crests, to name a few.

By the time his son, Chip, was a senior, the Bolles wooden stadium had seen better days and so Skinner spent several years fine-tuning his vision for a grand stadium — from designing and gathering other alumni support to overseeing the construction, and consistently adding to it glory since it first opened in November 1984.

“I visited other private schools in Chattanooga and Atlanta and came up with an idea for a design that sat high enough so that everyone could see the field well, even the bottom row,” he said. “As ideas were swirling, I came across an alumni who was a contractor and charitable enough to come in and rebuild, as well as several prominent supporters including Charlie Barco, for which the Skinner-Barco stadium is named.”

Skinner did not stop there, but has continued to design and build additions to the stadium in his backyard workshop, such as stadium lighting made from junkyard material, athletic storage and signage facilities, athletic display cases, entrance signage, and even the school’s San Jose Boulevard billboard. He even built an elaborate press box in four pieces that was delivered to the school with a crane and sits at the 50th yard line above the stands.

Last year, another one of Skinner’s visions was realized with the construction of the Corky Rogers Plaza – a new front entrance to the stadium located at the west side that also showcases Rogers’ legendary wins. It was unveiled last summer with both the Skinner and Rogers families gathered to commemorate the plaza. Skinner had befriended many of Bolles coaches and was especially fond of Rogers, who died in February and his Bolles football record.

Named a Bolles Trustee in 1961, Skinner was inducted into the Georgia Tech College of Carlton Engineering Hall of Fame in 1999. His brother, Brightman, who passed away last year at age 94 and sister, Mary Virginia Jones, who is 92, have all been honored for their significant philanthropy. Most recently, the University of North Florida renamed Buildings 3 and 4, which house classes and offices for various academic departments, after them.

Since Skinner’s attendance and graduation in 1940, all of the Skinner family including his children, grandchildren and now great grandchildren have gone to school at Bolles.

“Of all the experiences I’ve had and of the people who have helped me along the way, my father influenced me the most,” he said. “I look up to him for so many reasons, one his being the captain and quarterback on the Furman University team in Greenville, South Carolina.”

By Christina Swanson

Resident Community News

(16 votes, average: 3.75 out of 5)

(16 votes, average: 3.75 out of 5)